INTRODUCTION

Assessing the eyes of children can be difficult. To facilitate the assessment have the correct equipment, a knowledge of the common and the serious eye conditions in children, as well as what particular signs to look for at different ages, and what are the red flag signs to never to miss. All these components will make the assessment easier and safer. In this paper, we will review common eye problems in children and also those eye problems which are less common, but which have the potential to threaten sight or life. There will be a particular emphasis on the clinical assessment of babies and children aged 3-4 years.

COMMON PAEDIATRIC EYE CONDITIONS WITH THE POTENTIAL TO THREATEN SIGHT

AMBLYOPIA

Amblyopia is defined as reduced vision that cannot be attributed to a structural abnormality of the eye or the visual pathway. It is an important diagnosis to consider in children because it is potentially reversible if it is identified and treated, early. Amblyopia has several possible causes including

- Stimulus deprivation. For example, due to a cataract or ptosis that obscures the visual axis

- Asymmetry of refractive error (anisometropia). For example, if the right eye has 2 dioptres of hypermetropia and the left eye has 5 dioptres of hypermetropia, the left eye is likely to become amblyopic.

- For example, if the left eye is constantly esotropic, it is likely to become amblyopic.

The visual system in children is more ‘plastic’ than adults and amblyopia is the brain’s way of adapting (for example, to avoid double vision if the eyes are misaligned) or of being efficient (for example, by ‘shutting down’ the vision in an occluded eye). If identified in childhood, the plasticity of the visual system can be used to our advantage for treatment: when used in combination with treating the cause of the amblyopia, patching therapy forces the brain to ‘exercise’ the visual system of the amblyopic eye and can result in a significant improvement in vision. In children who do not tolerate a patch, atropine eye drops can be used to blur the vision in the good eye instead. Patching and atropine therapy should be initiated and supervised by an ophthalmologist as excessive treatment can result in unwanted side effects including ‘reverse amblyopia’ of the good eye. These treatments are most effective if initiated before the age of 7 years, but can have some effect after this.

STRABISMUS

Strabismus is a term describing any condition where the visual axes of the eyes are not aligned with each other. Strabismus has implications for vision and visual function and may have significant implications for a child’s social development and opportunity. Strabismus often runs in families and is frequently associated with refractive error. The most common types of ocular misaligment are:

- Esotropia – the non-fixing eye deviates in, toward the nose (‘cross-eyed’)

- Exotropia – the non-fixing eye deviates out, away from the nose (‘wall-eyed’)

- Hypertropia – the non-fixing eye deviates up

- Hypotropia – the non-fixing eye deviates down

The causes of a strabismus are numerous but those seen most commonly in children are:

- Congenital esotropia. The esotropia in these children onsets before the age of 6 months. Because the angle of the turn is large, these babies will often use their left eye to look at objects on their right side and use their right eye to look at objects on their left side. This phenomenon, called cross-fixation, protects them from amblyopia because they are using the vision in each eye alternately. These children tend to have no significant refractive error and the treatment is surgical, before the age of 12-24 months. Because surgery collapses the large angle, they no longer cross-fixate so post-operatively they are at risk of developing amblyopia, which may require patching or atropine therapy.

- Accommodative esotropia. Children born with a high AC:A ratio will develop an esotropia which is larger when looking at objects that are close (for example, when looking at a book). These children usually present aged 18 months – 3 years and require treatment with glasses (sometimes with bifocal lenses) and sometimes surgery. Features of both refractive and accommodative esotropia often co-exist and the treatment will reflect this.

- Refractive esotropia. It is very common for children to be hypermetropic (far sighted) and in the absence of any other eye disease, low-grade hypermetropia is considered normal and does not need to be treated with glasses. Children’s eyes can accommodate much more strongly than adult eyes so children who have significant hypermetropia (³4 dioptres) are able to pull most objects into focus but in doing so, they activate the accommodation reflex very strongly which may cause their eyes to converge (esotropia). Correcting the refractive error with glasses reduces the size and the frequency of the turn but some may require surgery to straighten any residual esotropia.

- Intermittent exotropia. In this condition, one eye intermittently drifts out during times of visual inattention (‘day-dreaming’) or fatigue, or when looking off into the far distance. An associated feature is the child will close the affected eye in the sunshine as it drifts out. Parents will often comment that they notice their child closes one eye when they are looking across a park or playground. The frequency of the turn can worsen with age and it is reasonable to consider surgery if the eye deviates more than half of the day or if the turn is having an impact on the child’s social development. Glasses that force the child to accommodate more strongly may be a temporizing treatment strategy. In a smaller subset of patients, the eye will drift out when looking at objects that are close and these children can be helped by exercises prescribed by an orthoptist, such as ‘pencil push-ups’, which help to strengthen ocular convergence. Because these conditions are intermittent they are rarely associated with amblyopia.

- Pseudo-strabismus. This is a common condition where the shape of the face or the conformation of the nasal bridge can give the impression that the eyes are misaligned. A cover test will demonstrate that the eyes are actually well aligned. This is particularly common in young children of Asian familial origin. It becomes less obvious as the child grows and the nasal bridge becomes higher.

- Duane’s syndrome. This is a cranial misinervation syndrome where the nerve supply to the lateral rectus muscle (usually supplied by the 6th cranial nerve and responsible for ABducting movements of the eye) doesn’t develop normally. The effects are multiple but the characteristic feature in all cases is retraction of the eyeball into the orbit (enophthalmos) causing the upper eyelid to drop slightly (pseudo-ptosis), on attempted ADduction of the affected eye.

- Brown’s syndrome. The tendon of the superior oblique muscle, responsible for elevating the eye when it is ADducted, passes through a bony and ligamentous pulley called the trochlea, which is located in the antero-supero-nasal orbit. In Brown’s syndrome, there is a mechanical restriction of the tendon’s movement through the trochlea. This results in failure of the eye to elevate when it is in the ADducted position.

- Sensory esotopia. An eye that sees poorly will usually become strabismic, regardless of the cause of the poor vision. In this way, amblyopia can be a cause of strabismus. All children with strabismus require a thorough examination to exclude a sensory cause, such as cataract or retinoblastoma. Although we do not fully understand why, children usually become esotropic in the context of reduced vision, whilst adults become exotropic.

- Congenital exotropia. Congenital exotropia refers to a constant exotropia present before the age of 6 months. It is rare in otherwise healthy infants. Many children with a constant exotropia have associated neurological or craniofacial disorders. Early surgical management may have a role in some cases.

- Nerve palsies. The extraocular muscles are controlled by cranial nerves III (the Oculomotor nerve, supplying the medial rectus, inferior rectus, superior rectus and inferior oblique muscles) IV (the Trochlear nerve supplying the superior oblique muscle) and VI (the Abducens nerve, supplying the lateral rectus muscle). In children, nerve palsies may be congenital or acquired. Acquired causes of a 3rd cranial nerve palsy in children include severe head trauma, central nervous system inflammation or neoplasm and migraine. A 4th nerve palsy is more commonly congenital and often presents with an altered head posture (the head tilts away from the affected side) but may also follow a closed head injury, even a mild one. A 6th nerve palsy may be related to infectious or inflammatory causes but in approximately one third of children it is associated with an intracranial mass lesion. The 6th nerve palsy is frequently the result of raised intracranial pressure.

TRAUMA AND CORNEAL FOREIGN BODIES

A child with a painful, injured eye can be particularly difficult to examine. It is appropriate to have a very low threshold for referral to an ophthalmologist, and it is advisable to consider keeping the child nil-by-mouth because an examination under anaesthesia is sometimes needed.

All ocular tissues, from the eyelids and ocular adnexae to the retina and the optic nerve are vulnerable to trauma. Taking a history to elicit the mechanism of injury is essential and helps to set the level of suspicion for severity and urgency. A high-speed projectile (such as something thrown up by the lawnmower) has a much greater potential for globe rupture than, say, an accidental self-blow to the eye with a piece of paper. Dog bites frequently lacerate the canalicular system responsible for draining tears from the ocular surface, which requires micro-surgical repair. The child’s post-injury behavior may be a clue to severity – a child with a globe rupture may keep their eye closed and resist all efforts to have it opened for assessment. It is important to consider an apparently small eyelid laceration may be the only obvious sign of significant orbital trauma (an accident with a wire coat-hanger can cause this type of injury).

Two common manifestations of ocular trauma are (i) corneal foreign body and (ii) corneal abrasion.

Corneal Foreign Body

When a foreign body gets stuck on the corneal surface it can cause redness, pain, watering, photosensitivity and reduced vision. Children with a corneal foreign body may keep the eyes closed.. Consider the following when assessing a child with a corneal foreign body and have a low threshold for referral to an ophthalmologist:

- A foreign body on the central cornea is more likely to be potentially vision-treatening than one on the peripheral cornea

- If there is any keratitis (indicated by corneal opacity surrounding the foreign body) the child may require intensive topical antibiotic therapy after removal of the foreign body

- If there is a history of projectile injury, consider the possibility that the ‘foreign body’ may actually be iris or other intraocular tissue plugging a small corneal wound.

Corneal epithelial defect

After a corneal foreign body has been removed, a small corneal epithelial defect will remain. Other common causes of a corneal epithelial defect are abrasions by an accidental scratch with a fingernail or piece of paper or being hit in the face with a tree branch. The abrasion will fluoresce green, under the cobalt blue light setting of the ophthalmoscope, after installation of fluorescein drops in the eye. The tear film and lid margins will also glow green because fluorescein pools in these areas. If there is no associated keratitis, a corneal abrasion can be treated with a topical antibiotic drop such as chloramphenicol, 1 drop given 4 times per day for 5-7 days. The signs and symptoms usually resolve completely within 48 hours. If there is any suggestion of keratitis or if signs and symptoms persist beyond 48 hours, referral to an ophthalmologist may be warranted.

KERATITIS

Keratitis refers to inflammation involving the cornea. The clinical features include reduced vision, redness, photophobia, watering and corneal clouding (which may be subtle and not seen without a slit-lamp). There may be an associated corneal epithelial defect. Keratitis may be infective or non-infective.

Infective keratitis

Herpes simplex virus keratitis is the most common cause of infective keratitis in children. This requires referral to an ophthalmologist as the sequelae can be complicated and recurrent. Sequelae include vision threatening corneal scarring which may require surgical management, corneal anaesthesia, secondary bacterial keratitis, uveitis and secondary glaucoma.

Bacterial keratitis is much less common in children than in adults. It can occur in the context of trauma or contact lens wear. Contact lenses are prescribed to some children by ophthalmologists for correction of refractive error in the context of ophthalmic disease such as following congenital cataract surgery, or in the management of severe ocular surface disease such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Cosmetic or novelty contact lenses and orthokeratology contact lenses for the management of mild degrees of refractive error are not advisable in children.

Non-infective keratitis

Blepharokeratoconjuntcivitis (eyelid, corneal and conjunctival inflammation) is an ocular surface hypersensitivity reaction to the normal eyelid flora. This falls into the rosacea spectrum of conditions. The condition is often bilateral but asymmetrical and the history will be one of intermittent redness and mild ocular irritation over the course of several weeks or months.

The child may be intermittently photosensitive and have intermittent watering of the eye. Ocular examination will show inflammation of the eyelid margins and inspissation of the Meibomian gland openings (which can be much less obvious in children compared with adults), mild and non-specific conjunctival hyperaemia and corneal opacity in areas where it is contact with the eyelid margin. There is often a small epithelial defect overlying the area of corneal opacity. Treatment may involve lid hygiene measures (warm compresses and lid scrubs with dilute baby shampoo), topical antibiotics, a short course of topical steroids, and a long course of systemic antibiotics such as low-dose erythromycin for its anti-metalloproteinase actions.

COMMON PAEDIATIC EYE CONDITIONS UNLIKELY TO THREATEN SIGHT

NASOLACRIMAL DUCT OBSTRUCTION

The usual pathway for draining tears from the ocular surface starts at the punctum of the inner eyelid. Tears drain through the puncta into the upper and lower canaliculi, which empty into the lacrimal sac. The lacrimal sac drains into the nasal cavity via the nasolacrimal duct. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction is common and may be identifiable at the 6-8 week baby check. It may be unilateral or bilateral and parents will notice the eye is sticky or watery every day. It is important to consider and assess for other causes of a watery eye in a neonate, such as congenital glaucoma, in which the cornea may appear cloudy and the child will be photophobic. Children with NLDO are not photophobic.

The majority (>90%) of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstructions resolve within the first year of life with conservative treatment, comprising massage of the lacrimal sac (see separate box). Topical antibiotics are not routinely required: they are only indicated if there is associated infection of the conjunctiva.

Those that do not resolve with conservative treatment may need probing of the nasolacrimal duct by an ophthalmologist. This is usually done within the first 12-24 months of life, requires a brief general anaesthetic and is often successful in opening the obstruction after a single procedure. If it recurs despite more than one successful probing, the nasolacrimal duct may require intubation with silicon tubing. The tubes are left in place for several weeks or months to help ‘stent’ the system open, at which stage they can be removed.

Complications of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction are uncommon. They can include conjunctivitis, a dacryocystocoele (a collection of sterile fluid in the lacrimal sac seen as a blue-coloured mass overlying the lacrimal sac in newborn babies) or dacryocystitis (infection of the lacrimal sac fluid collection). A dacryocystoceole may require probing in the neonatal period if it is not reducible, as the risk of developing a dacryocystitis is high. Dacryocystitis usually requires admission to hospital for intravenous antibiotics and may also require early probing.

CONJUNCTIVITIS

Conjunctivitis is one of the most common paediatric eye problems. It can be difficult to accurately distinguish the cause of the conjunctivitis and thereby initiate the correct treatment. Any conjunctivitis in a neonate is an ophthalmic emergency and should be referred to an ophthalmologist for assessment and treatment. Neonatal conjunctivitis is considered to be gonococcal, chlamydial or herpetic (transmitted from the birth canal) until proven otherwise.

Viral conjunctivitis

Most cases of viral conjunctivitis are caused by adenovirus. This DNA virus is also associated with upper respiratory infections and gastroenteritis and the conjunctivitis may occur in conjunction with these systemic diseases. The conjunctivitis is usually bilateral (often sequential), sometimes it is haemorrhagic, and the discharge is usually watery. A pre-auricular lymph node may be palpable. The diagnosis can be confirmed by taking a conjunctival swab for adenovirus PCR although this is usually not indicated. Some may elect to treat with a topical antibiotic (such as chloramphenicol, 1 drop, QID to both eyes) until the conjunctivitis resolves, to prevent a secondary bacterial infection. Older children who are not averse to using eye drops may get symptomatic relief from also using an over-the-counter preservative-free lubricating eye-drop as required. Most importantly, educate the family on strategies to minimize transfer within the family eg. hand washing before and after instilling eye drops, using separate towels etc. Being highly contagious, be sure to clean your hands and examination room thoroughly!

Bacterial conjunctivitis

Bacterial conjunctivitis is very common in school-aged children, with Streptococcus, Haemophilus and Moraxella being the commonest causative organisms. Cases present with unilateral of bilateral conjunctival hyperaemia, purulent discharge and a history of the eyelids being sealed closed with discharge upon waking. Conjunctival swabs are usually not indicated as most cases resolve with a 10 – 14 day course of broad-spectrum topical antibiotics, used 4-6 times per day.

Allergic conjunctivitis

There are many subtypes of ocular allergy, all attributable to a Type 1 hypersensitivity reaction, with the following clinical features in common: Bilateral conjunctival injection and swelling with chronic, relapsing-remitting nature, possibly with seasonal recurrence and thick, ropy discharge. The upper tarsus may become covered in irregular lumps (giant papillae) and in more severe forms, the cornea can ulcerate. The most consistent feature and the symptom that is most highly suggestive is redness and itchiness. Not all will have a history of atopic disease as ocular allergy can exist in isolation. Treatment involves eliminating the offending allergen (if known) and reducing allergen concentration by washing the face, brows and lashes regularly. Topical mast cell stabilizers (eg. topical Olopatadine or Ketotifen, 1 drop BID both eyes) can be effective in preventing and treating seasonal flare-ups but they take 6 weeks to have their full effect and should not be used for longer than 3 months at a time. Topical steroids and topical immunomodulators are useful and should be prescribed after a comprehensive ophthalmological assessment including intraocular pressure assessment.

PRESEPTAL CELLILITIS

reseptal cellulitis is a common infection in children, which affects tissues anterior to the orbital septum. It is nearly always associated with an upper respiratory tract infection or sinusitis. Less commonly it may follow skin trauma (an insect bite or a scratch) or conjunctivitis. The periorbital skin becomes erythematous and swollen and the child may be systemically unwell with a fever. If the child is over the age of 2 and is systemically well, a course of oral systemic antibiotics is usually sufficient treatment, along with treatment of the predisposing condition including nasal decongestion. If the symptoms do not improve over 24-36 hours then the child should be referred for intravenous antibiotics. Early treatment is critical to reduce the risk of progression to orbital cellulitis.

UNCOMMON PAEDIATRIC EYE CONDITIONS WITH THE POTENTIAL TO THREATEN SIGHT AND LIFE

ORBITAL CELLULITIS

Orbital cellulitis is an infection which affects the tissues of the orbit (posterior to the orbital septum). It may follow an upper respiratory infection (particularly in the context of sinusitis), facial trauma or be idiopathic. It presents with lid oedema, erythema, and pain. The child is almost always systemically unwell with fever and lethargy. Because the tissues of the orbit are affected, it may be associated with diplopia, reduced vision, proptosis and a limitation of eye movements. The presence of any of these signs necessitates urgent referral to an ophthalmologist or emergency department for initiation of broad-spectrum IV antibiotics. If there is an abscess and an imminent threat to vision, the child may require surgical drainage of the orbital collection as a matter of urgency. The complications of orbital cellulitis include life-threatening diseases such as meningitis or brain abscess.

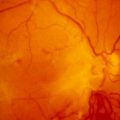

RETINOBLASTOMA

Retinoblastoma is the most common malignant ocular tumour of childhood. It is typically diagnosed within the first 3 years of life and is extremely rare to present after the age of 5 years. Retinoblastoma is due to a mutation in the RB1 gene (a tumour suppressor gene). In familial (hereditary) cases the child is born with a mutation in one copy of the RB1 gene in every cell of their body. A mutation in the second copy of the RB1 gene in an immature retina cell results in the development of a retinoblastoma. Because the second mutation is a relatively common event, the usual pattern is for multiple tumours to develop in both eyes, in familial cases. Familial cases are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

Because children with a hereditary or germline RB1 mutation have the mutation in every cell of their body, they are at high risk of developing other tumours such as sarcomas, breast cancer, lung cancer and lymphoma. For this reason, these patients should AVOID radiation in the form of CT scans or X-Rays to ANY part of their body. MRI and ultrasound are the preferred imaging modalities.

In non-hereditary cases, a single cell needs to undergo a mutation in both of its RB1 genes. Because this is a relatively rare event, non-hereditary cases tend to be unilateral. Knowing whether the retinoblastoma is hereditary or non-hereditary, and identifying the exact gene mutation by sequencing the gene is extremely powerful in the appropriate management of affected children and their families. All patients with retinoblastoma should have genetic counselling. This facilitates identifying the risk for other family members and helps to direct surveillance for additional tumours. This is important as a parent may be an asymptomatic carrier and so the risk for further children is then increased to 50%..

Retinoblastoma may present to the general practitioner as leukocoria (some parents will first notice the white pupillary reflex in photographs) or strabismus. Less common presentations may include a cloudy cornea or a hyphaema (blood in the anterior chamber). Any sign suggestive of retinoblastoma should be referred urgently to an ophthalmologist. Retinoblastoma is managed with a multidisciplinary approach and treatment may include enucleation (surgical removal of the eye), laser or cryotherapy to intraocular tumours, local and systemic chemotherapy.

CATARACT

Approximately 6 per 10,000 children are affected by cataract. Paediatric cataracts may be unilateral or bilateral, isolated or part of a systemic disease, congenital or acquired, familial or sporadic. Most familial cataracts are autosomal dominant so it is prudent to refer the children of patients with a history of congenital cataract for assessment within the first few weeks of life. Prompt diagnosis and management can avoid life-long vision impairment, which is why making an assessment of the red-reflex at the 6 week baby check is such a powerful clinical test. A dull red reflex, any asymmetry of the red reflex or any leukocoria requires urgent referral to an ophthalmologist. Management often involves surgical extraction followed by intraocular lens implantation and/or glasses and/or contact lenses.

GLAUCOMA

Glaucoma can present at any age and may even be present at birth. The childhood glaucomas represent a very broad disease spectrum and may be primary (due to an inborn anomaly of the aqueous outflow pathway) or secondary (due to some other ocular abnormality or systemic disease). Because the wall of the eye is much more pliable in children, glaucoma presents very differently when compared to adults: High intraocular pressures in children causes the eyewall to stretch, which can result in buphthalmos (where the eye becomes larger and progressively more myopic, the first sign may be the child has “beautiful big eyes”). Stretching of the cornea causes it to cloud which may be visible on your examination. Corneal clouding often causes the child to become photophobic and the eyes may water frequently. The clinical signs may be asymmetrical.

The glaucoma that presents in neonates and infancy is usually autosomal recessive which then indicates a risk to further siblings. The latter onset glaucoma in childhood is often autosomal dominant, so children of patients with a history of juvenile-onset glaucoma should be screened for glaucoma. Clinical genetics assessment is important for these groups of children to assist in identifying the genetic cause and providing management regarding recurrence risk and reproductive options.

Any child with photophobia and watering, or with corneal clouding should be referred promptly for ophthalmic assessment. The treatment is often surgical and may be augmented with topical and systemic glaucoma therapy.

CONCLUSION

Examining the eyes of children can be very challenging for a variety of reasons: children may be reluctant participants in the examination or they may be unwell or in pain. Having your own equipment with which you are familiar, and having an effective and careful examination technique will mean serious clinical signs such as reduced vision, corneal clouding and leukocoria are not missed. The timely diagnosis of paediatric eye disease has sight-saving benefits and in some cases it is life-saving also.

This article was originally published in Australian Doctor.